“Dan Dennett was an inspiring human being . . .

we should all try to be a little more like Dan.”

~ Joshua Rothman

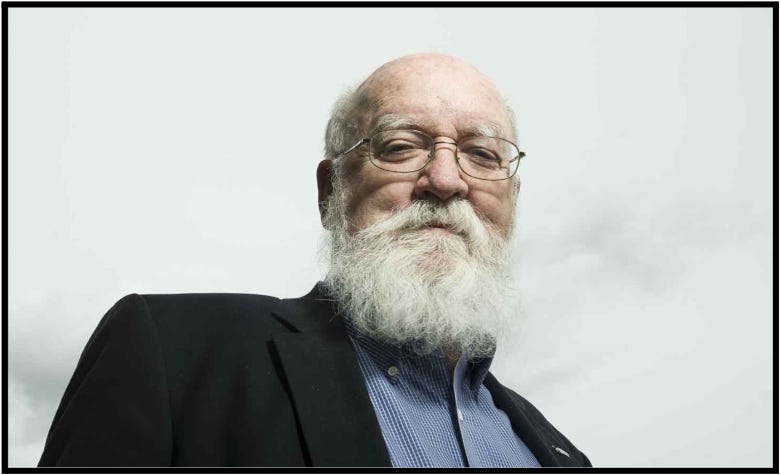

Dan Dennett died this past Friday. He was 82.

A philosopher famous the world over for his contributions to consciousness, evolutionary biology, free will, and religion, Dennett loved life on a grand scale. He dabbled in art, cider making, music, pottery, square dancing, tractor driving, trout fishing, whittling, windsurfing and more.

Two years ago I wrote about Dennett in this newsletter. When I mention someone, I usually send them the link. Often they write back. I can honestly say, of all the people that have responded, the one that got me the most excited was Dan Dennett.

It was like my childhood self getting a phone call from a rock star.

Even though he wrote me just one word. Just four letters (seven if you count the three initials he used to sign his name):

Good.

DCD

It’s funny looking at his response now and thinking back to how delighted it made me. I wonder, why do I hold him in such high regard?

To be clear, I’m not a philosopher, scientist, or academic. I’m an entrepreneur that helps people with high-stakes public speaking. What is it about Dennett??

I think it was his approach to life.

Five things in particular he did that I deeply admire. The purpose of this tribute is to highlight them all. (Dennett’s good friend Steven Pinker is writing an obituary that will give proper ode to his intellectual achievements.)

The Dennett approach I lay out is what I aspire to for myself and our clients. I encourage every reader to consider them. If we all applied these principles, we would instantly elevate the world.

#1. Seek Truth and Have Fun Doing It

Truth matters.

Civilization rests on the foundation of an objective understanding of the world. Truth is essential for societal, scientific, and cultural progress.

And yet, as Dennett warned us, truth can be a difficult road that is “competing with seductive easier paths that turn out to be dead ends. Most of the effort in thinking is a matter of resisting these temptations.” The postmodern idea that truth is relative is insidious, Dennett says, and has infected a generation of academics.

Days before he died, Big Think released a video called The Four Biggest Ideas in Philosophy, with Legend Daniel Dennett, where he says: “One of the most toxic ideas we are awash with right now is the idea that truth doesn’t matter.”

For nearly six decades Dennett dedicated his professional life to defending, searching for, and teaching the truth. And unlike most philosophers, he made the search for truth thrilling.

In the opening paragraph of The Minds I, Dennett writes:

You are on Mars, millions of miles from home, protected from the killing, frostless cold of the red Martian desert by fragile membranes of terrestrial technology.

He immediately pulls us into a mind-bending story that leaves us wondering who we are, and then “promises to lead you on a voyage of discovery of the self and the soul.” Dennett dedicated not only this book, but his entire career, to doing exactly that.

His iconic essay Where Am I? begins like this:

Now that I’ve won my suit under the Freedom of Information Act, I am at liberty to reveal for the first time a curious episode in my life . . . several years ago I was approached by Pentagon officials who asked me to volunteer for a dangerous and secret mission.

In this brilliant, bizarre (fictional) story, we learn that his brain was removed from his body and connected to it with a radio transmitter. We are forced to wonder where “he” truly resides: in the brain, or the body?

Here am I, Daniel Dennett, suspended in a bubbling fluid, being stared at by my own eyes.

This essay teaches truths about the nature of consciousness, yet is so compelling it was made into a movie:

Hardly the boring abstract philosopher! Truth is fascinating, objective, and attainable – yet we should always remain humble in how certain we are we’ve discovered it.

#2. Share Stories with Morals

The philosopher Aristotle is known as the Father of Logic and also a huge advocate for storytelling. He taught that stories are crucial for helping us communicate abstract ideas and feelings.

Dennett was a master at this. He used all kinds of stories, and his favorite may have been brief vignettes he called intuition pumps.

As he says in How to Think Like a Philosopher:

Intuition Pumps are stories, they’re little fables, similar to Aesop’s Fables, they’re supposed to have a moral, they’re supposed to teach us something. They lead the audience to an intuition, a conclusion where you pound your fist on the table and say, “yeah it’s gotta be that way!”

And if it’s achieved that, it’s pumped the intuition it was designed to pump. These are little persuasion machines that philosophers have been using for several thousand years.

His book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking is filled with these persuasion machines – exciting stories with clear morals. We encounter Zombies and Zimboes, a Truly Nefarious Neurosurgeon, and a Swampman Meeting a Cowshark. We investigate a murder in Trafalgar Square, get Trapped in a Robot Control Room, and wonder what happened to The Ballad of Shakey’s Pizza Parlor.

Instead of a typical philosopher writing with dry, abstract academic jargon, Dennett brings his audience on weird and wild adventures in search of truth. Even in his book on free will, Elbow Room, we travel to alien worlds with special robots to help us discover our moral responsibilities on Earth.

And alliteration! He understood we humans love alliteration in our stories. So deep-thinking Dan Dennett deftly duplicated the stylistic steps of sophisticated storytellers like Shakespeare, Plath, and Poe in liberally lavishing his love of alliterative allure upon us diligent devotees. Consider:

From Bacteria to Bach and Back; the Boys from Brazil; a community of communicators; Competence without Comprehension; their conjunction is itself clearly conceivable; Content and Consciousness; the Curse of the Cauliflower; Daddy is a Doctor; Darwin’s Dangerous Idea; the Dread Secret Denied; Quining Qualia; Making Mistakes; Nihilism Neglected; a similarly shaped something; What’s So Special about Species?; The Sword in the Stone; and, as already acknowledged, Zombies and Zimboes.

Perhaps his favorite topic to teach was Darwinian natural selection, which he brought to life through skyhooks and cranes.

#3. Look Beyond the Skyhooks to See the Cranes

Dennett died on April 19, connecting him even closer to his intellectual hero, Charles Darwin, who passed away on the same date 142 years earlier. He writes in my favorite book of his, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea:

Let me lay my cards on the table. If I were to give an award for the single best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else. In a single stroke, the idea of evolution by natural selection unifies the realm of life, meaning, and purpose with the realm of space and time, cause and effect, mechanism and physical law.

Darwinian natural selection is the “crane” that actually builds the natural world around us. Cranes work steadily, piece-by-piece, from the ground up. Over time, they produce giant complex works from extremely simple parts.

Cranes extend beyond nature. Consider computers. They are made from transistors with two options: connect or disconnect. 0 or 1. Yet from this simple binary arises the infinite complexity and power of our modern digital world.

Kurzgesagt has a beautiful video explaining cranes (also known as emergence):

By contrast, “skyhooks” are magical devices that can’t bear weight because they hang from nothing. Ideas that lack evidence hang from “skyhooks” and cannot honestly lead us to the truth.

At one point, every culture on Earth was steeped in skyhooks: The Chinese believed Dragon Kings manipulated ocean currents; The Egyptians believed Bastet summoned gentle breezes with the flick of her tail; The Japanese believed Raijin created lightning by beating drums; and Europeans believed seizures were caused by demons.

A key to finding the truth is to look beyond the skyhooks and discover the real builders, the cranes.

“If we had to choose one man to represent Earth in a debating tournament with extraterrestrials, the American philosopher Daniel Dennett would be a prime candidate.”

~ Matt Ridley

#4. Apply Rapoport’s Rules

Sometimes I think about this tweet from Keith Olbermann, where he calls Joe Rogan the dumbest person on the planet.

It’s emblematic of a popular approach to dealing with people we disagree with. Simply attack them with anger. Call them names and distort or ignore the nuance of their arguments.

Dennett popularized a different approach. He called it Rapoport’s Rules after Anatol Rapoport, a polymath and pioneer in game theory.

Rapoport studied human conflict and wrote about three approaches (more sophisticated than the Olbermann name calling method) people can take when seeking to criticize another’s views. Rapoport named them after influential psychologists:

The Freudian: Reveal “hidden motives” behind your opponent’s thoughts. Explain them away as unconscious beliefs.

The Pavlovian: See if you can “shape and control” the person through punishments or rewards.

The Rogerian: Seek to “genuinely understand” their position. Be accepting rather than judgmental. Look for merit and similarities to your views.

The Rogerian is named after Carl Rogers, a pioneer in effective listening:

When someone really hears you without passing judgment on you . . . without trying to mold you, it feels damn good. . . . confusions which seem irremediable turn into relatively clear flowing streams when one is heard.

Rapoport built on Rogers’ insight and came up with an approach for dealing with people who think differently. Dennett dubbed it Rapoport’s Rules:

LISTEN: Have the other person share their perspective. Allow them to fully exhale. Don’t interrupt. Give them your full attention.

UNDERSTAND: Ask clarifying questions. Seek to genuinely understand what they think.

RESTATE: Use your own words to describe their position. Do it so well they say “that’s right!” Or even better, “I wish I said it that clearly.”

AGREE: Let them know everything from their position you agree with.

LEARN: Clarify anything they said you didn’t know. Tell them what they taught you.

Only after following this process are we permitted to state our disagreements. Ideally, we are asked to share them. We focus on respectfully refuting their central point rather than attacking them personally or using emotionally charged criticisms.

Rapoport’s Rules help us to come across as a friend rather than an enemy. An honest adult rather than a petulant child. People are far more likely to listen to us in return and consider our ideas.

Dennett worked hard to apply Rapoport’s Rules. He treasured the response he got from a philosopher who he “profoundly” disagreed with. He explained both their views in a book and received this response:

The treatment of my view is extensive and generally fair, far more so than one usually gets from critics. You convey the complexity of my view and the seriousness of my efforts . . . I am grateful.

Listen to how Dennett discusses the pastor Rick Warren, another person he profoundly disagreed with:

Compare Dennett’s approach to Keith Olbermann’s. Ask yourself, which do you want to emulate?

Even though Dennett was an atheist, he began Darwin’s Dangerous Idea by taking us to a religious summer camp from his childhood. We see him sitting around a fire, singing a song about God. He tells us the song “still brings a lump to my throat . . . I want to protect the campfire song, and what is beautiful and true in it, for my little grandson and his friends, and for their children when they grow up.”

Later in the book he clarifies: “Not all scientists and philosophers are atheists, and many who are believers declare that their idea of God can live in peaceful coexistence with, or even find support from, the Darwinian framework of thinking.”

A year after Darwin’s Dangerous Idea was published, then-Pope John Paul II (who, like Dennett, was a respected philosopher with a deep interest in science) gave a speech aligned with Dennett’s insight: “there is no conflict between evolution and the doctrine of the faith.”

Importantly, Dennett’s respectful approach did not make him a pushover or people pleaser. He was known for his lively debating, for standing up for his beliefs, and for famously sparring with scientists and philosophers – notably his longtime intellectual rival Stephen J. Gould.

And yet, even with Gould, he worked hard to apply Rapoport’s Rules.

#5. Thank Goodness!

In 2006, Dennett had a near death experience.

He was rushed to a hospital and underwent a nine-hour surgery. Upon awakening, he wrote a famous article titled Thank Goodness!

The idea is to give thanks for all the human-made goodness surrounding us. He wrote:

There is a lot of goodness in this world, and more goodness every day, and this fantastic human-made fabric of excellence is genuinely responsible for the fact that I am alive today. It is a worthy recipient of the gratitude I feel today, and I want to celebrate that fact here and now.

To whom, then, do I owe a debt of gratitude? To the cardiologist . . . . To the surgeons, neurologists, anesthesiologists, and the perfusionist. . . .To the dozen or so physician assistants, and to nurses and physical therapists and x-ray technicians and a small army of phlebotomists . . . .

These people came from Uganda, Kenya, Liberia, Haiti, the Philippines, Croatia, Russia, China, Korea, India—and the United States, of course—and I have never seen more impressive mutual respect, as they helped each other out . . . .

When we look around, we can find awe-inspiring goodness and beauty everywhere. The entire natural world as well as “this fantastic human-made fabric of excellence” including all the amazing things humans build.

And not just life-saving hospital equipment and grand bridges and space stations – even a simple pencil induces awe and wonder. I highly encourage you to watch this beautiful video by the Competitive Enterprise Institute that encapsulates the essence of Dan Dennett:

Not a single person can skyhook even a pencil into existence. The capital-T Truth about our species is this: a fantastic human-made fabric of cooperative excellence on a mind-bending scale is the ultimate crane of our progress.

To the billions of people that built our modern world, and all the stuff we enjoy in it, Thank Goodness for them all.

And Thank Goodness for the world that Dan Dennett lived.

“I really loved him, loved his spirit, his generosity, the expansiveness of his thinking, his delight in ideas, and his great good cheer. Philosophically, I think he had true greatness. It seems impossible he is gone.”

~ Johns Hopkins philosopher Jenann Ismael