“The heart of the nation is still sound and strong.”

~ Frederick Douglass

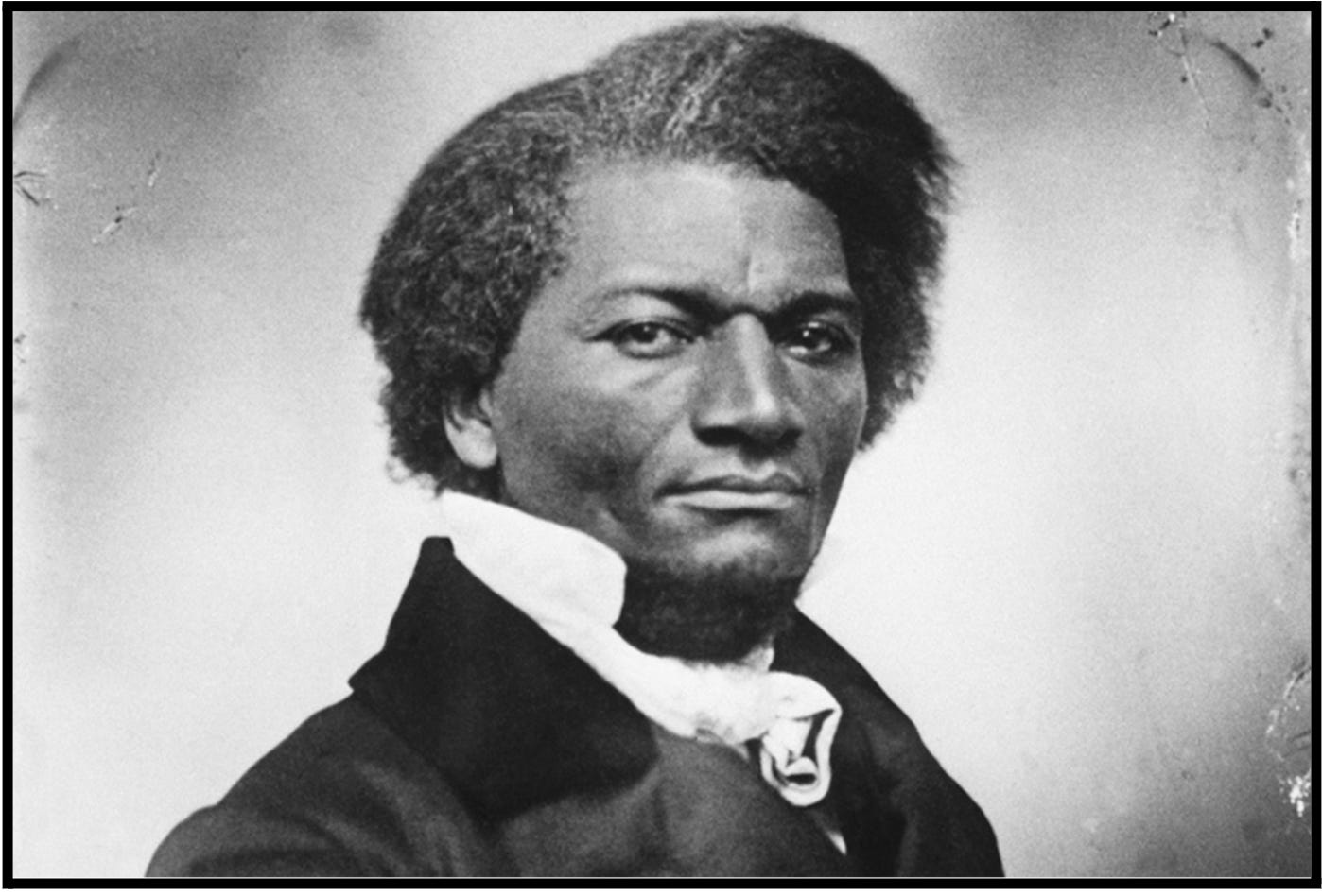

I’d like to share with you an iconic Memorial Day speech delivered by the best speaker in American history: Frederick Douglass.

A former slave turned civil rights leader, world-renowned for his brilliant oratory, Douglass delivered There Was a Right Side in the Late War: An Address on a rainy, windy Memorial Day in 1878, when the Civil War and the stain of slavery were still fresh. According to The Frederick Douglass Papers Project:

The assembly grew silent as Douglass approached the platform railing but “broke into enthusiastic shouts” when, at the beginning of his oration, he dramatically raised his hand toward the nearby statue of Lincoln.

How I wish I were there to experience it!

There are countless insights we can draw from this speech, which I present below in its entirety. I will highlight three lessons we can apply to all our speaking, from formal occasions to our everyday conversations.

1. Exhibit Moral Clarity

Douglass knew it wasn’t enough to express his anger at the hypocrisy of our government and the evil committed by slave owners. He transcended outrage to show with clarity and compassion the correct path forward:

“There is in my heart no taint of malice toward the ex-slaveholders . . . the hand of friendship and affection which I recently gave my old master on his death-bed I would cordially extend to all men like him.”

2. Use Analogies and Vivid Imagery

The scientists Emmanuel Sander and Douglas Hofstadter explain that “the human ability to make analogies lies at the root of all our concepts . . . analogy is the fuel and fire of thinking.”

Douglass understood this and filled his speech with analogies and vivid imagery. Consider:

“I admit that the South believed it was right, but the nature of things is not changed by belief. The Inquisition was not less a crime against humanity because it was believed right by the Holy Fathers.”

“Men are not changed from lamb into tiger instantaneously….”

“It was not a fight between rapacious birds and ferocious beasts . . . it was a war between men.”

3. Be Optimistic about Building a Better World

Douglass experienced brutality most of us can scarcely imagine. Yet he remained an optimist who loved America’s founding ideals and believed we could work together to build a better world.

He concluded his Memorial Day speech with this:

“The heart of the nation is still sound and strong, and as in the past, so in the future, patriotic millions, with able captains to lead them, will stand as a wall of fire around the Republic, and in the end see Liberty, Equality, and Justice triumphant.”

The crowd erupted in applause as Douglass finished. The New York Times raved about his “statesmanship and the insight into the spirits of human action.”

Douglass would go on to become the 19th century’s most photographed American and perhaps its most powerful voice for the voiceless, advancing women’s rights after he succeeded in helping to abolish slavery.

***

There Was a Right Side in the Late War: An Address

New York, New York

30 May 1878

FRIENDS AND FELLOW CITIZENS:

In this place, hallowed and made glorious by a statue of the best man, truest patriot, and wisest statesman of his time and country, I have been invited—I might say ordered—by Lincoln Post of the Grand Army of the Republic, to say a few words to you in appropriate celebration of this annual national memorial day.

Deeply sensible of the honor thus conferred, and properly impressed with the dignity of this occasion, I accept the invitation cheerfully and gratefully; but not so much as an honor to myself, as a generous recognition of that class of our fellow-citizens to which I belong; a class hitherto excluded by popular prejudice from prominent participation in the memorial glories of our common country. Lincoln Post—most worthily named—will pardon me if I stop right here to commend it for this innovation upon an old custom; for its moral courage and soldierly independence. Abraham Lincoln was the first President of the United States brave enough to invite a colored gentleman to sit at table with him, and the post that bears his honored name is the first in this great City to invite any colored man to deliver an address on national memorial day.

But the duty you have imposed upon me is far more honorable in the distinction it confers upon me and my race, than easy of happy and successful performance. All that can be pertinently said on this occasion, has been said a thousand times before, and a thousand times better said, than anything I can now hope to say. Besides, and above all, the noble qualities and achievements to which we are here to do honor are of an order which transcends the narrow compass of speech. The eloquence of the most gifted orator of our country would fail to fitly and fully illustrate the heroic deeds and virtues of the brave men who volunteered, fought, and fell in the cause of the Union and freedom. “For greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” The topmost height of this greatness was touched by those who, in our national extremity, nobly died, that our Republic might live. We need something broader, more striking and impressive than speech, to express the thoughts and feelings proper to these memorial occasions. We need banners, badges, and battle flags; drums, fifes, and bugles; signs, sounds, and symbols; the clang of church-going bells; the heaven-shaking thunder of cannon; the steady and solemn tramp of armed men; the pomp and circumstance of glorious war; the shouts of a great nation rejoicing in its salvation, to express a proper sense of the worth of men to whose patriotic devotion and noble self-sacrifice the integrity of the nation and the existence of free institutions on this great continent are due.

SCENES THE DAY RECALLS.

For such high discourse, pageantry is better than oratory. It can be heard and seen by all. It speaks alike to the understanding and the heart. It carries us dreamily back to that dark and terrible hour of supreme peril, when the heart and the hope of a great people were smitten, stunned, and almost crushed by the stern pressure of a determined and wide-spread rebellion; when the enemies of free government all over the world watched, waited, desired, and expected the downfall of the grandest Republic in the world. It tells us of a time of trial and danger, when the boldest held their breath and the hearts of strong men failed them through fear; when the very earth seemed to crumble beneath our feet; when the sky above us was dark, and sinister whispers filled the air; when one star after another in rapid succession shot madly from the blue ground of the national flag, and this grand experiment of self-government, not yet 100 years old, torn and rent by angry passions, had fallen asunder at the centre, and our once united country was converted into two hostile camps. It is well once a year to contemplate that dismal panorama. But not alone to the gloom and disaster of rebellion and treason does this

grand display recall us. It is the province of rampant evil to call out the latent good, and this day reminds us of the good as well as of the evil. It reminds us of patriotic fervor, of quenchless ardor, of heroic courage, of generous self-sacrifice, of patience, skill, and fortitude, of clearness of vision to discern the right, and invincible determination to sustain it at every cost. It brings to mind the time when each day of the week saw

thousands of brave men in the full fresh bloom of youth and manly vigor, the very flower and hope of the hearths and homes of the loyal and peaceful North, deliberately sundering the ties that bound them, leaving friends and families, and periling all that was most precious to them for the sake of their country. The spectacle was solemn, sublime, and glorious, and will never be forgotten. New-York was the grand centre where these patriotic legions rallied. They arrived and departed through her hundred gates of sea and land. They came from the East, the West, and the North; from the Empire State with its millions of people; from the Old Bay State, the heart and brain of New-England, the State of Sumner, Andrew, and Wilson; from the icy slopes and beetling crags of stalwart Maine; from the beautiful lakes, winding rivers, and granite hills of New Hampshire, where Webster was born, and the spirit of John P. Hale still

lives; from the Green Mountains of Vermont, whence no slave, panting for liberty, was ever returned, to his master; from the land of Roger Williams, and the land of steady habits; from counter, farm, and factory; from schools, colleges, and courts of law they came; they came with blue coats on their backs, with eagles on their buttons and muskets on their shoulders, timing their high foot-steps to the music of the Union, and making the streets of this great Metropolis like rivers of burnished steel.

Never was there a grander call to patriotic duty, and never was there a more enthusiastic response to such a call; and both the call and the response showed that a Republic with no standing army to fight its battles, could, nevertheless, safely depend upon its patriotic citizens for defense and protection in any great emergency of peril. Brave and noble spirits! Living and dead! May your memory never perish! We tender you on this memorial day the homage of the loyal nation, and the heartfelt gratitude of emancipated millions. If the great work you undertook to accomplish is still incomplete; if a lawless and revolutionary spirit is still abroad in the country; if the principles for which you bravely fought are in any way compromised or threatened; if the Constitution and the laws are in any measure dishonored and disregarded; if duly elected State Governments are in any way overthrown by violence; if the elective franchise has been overborne by intimidation and fraud; if the Southern States, under the idea of local self-government, are endeavoring to paralyze the arm and shrivel the body of the National Government so that it cannot protect the humblest citizen in his rights, the fault is not yours. You, at least, were faithful and did your whole duty.

THE EMBERS OF THE REBELLION.

Fellow-citizens, I am not here to fan the flame of sectional animosity, to revive old issues, or to stir up strife between races; but no candid man, looking at the political situation of the hour, can fail to see that we are still afflicted by the painful sequences both of slavery and of the late rebellion. In the spirit of the noble man whose image now looks down upon us we should have “charity toward all, and malice toward none.” In the language of our greatest soldier, twice honored with the Presidency of the nation, “Let us have peace.” Yes, let us have peace, but let us have liberty, law, and justice first. Let us have the Constitution, with its thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments, fairly interpreted, faithfully executed, and cheerfully obeyed in the fullness of their spirit and the completeness of their letter. Men can do many things in this world, some easily and some with difficulty; but there are some things which men cannot do or be. When they are here they cannot be there. When the supreme law of the land is systematically set at naught; when humanity is insulted and the rights of the weak are trampled in the dust by a lawless power; when society is divided into two classes, as oppressed and oppressor, there is no power, and there can be no power, while the instincts of manhood remain as they are, which can provide solid peace. I do not affirm that friendly feeling cannot be established between the people of the North and South. I do not say that between the white and colored people of the South, the former slaves and the former masters, friendly relations may not be established. I do not say that Hon. Rutherford B. Hayes, the lawful and rightful President of the United States, was not justified in stepping to the verge of his constitutional powers to conciliate and pacify the old master class at the South; but I do say that some steps by way of conciliation should come from the other side. The prodigal son should at least turn his back upon the field of swine, and his face toward home, before we make haste to fall upon his neck, and for him kill the fatted calf. He must not glory in his shame, and boast his non-repentance. He must not reenact at home the excesses he allowed himself to commit in the barren and desolate fields of rebellion. The last commanding utterance of Southern sentiment is from the late President of the Southern Confederacy. He says: “Let not any of the survivors [of rebellion] impugn their faith by offering the penitential plea that they believed they were right.” There is reason to believe that Jefferson Davis, in this, speaks out of the fullness of the Southern heart, as well as that of his own. He says, further, that “Heroism derives its lustre from the justice of the cause in which it is displayed.” And he holds, and the South holds as firmly to-day as when in rebellion, the justice of that cause, and that a just cause is never to be abandoned.

THE FEELINGS OF THE COLORED RACE.

My own feeling toward the old master class of the South is well known. Though I have worn the yoke of bondage, and have no love for what are called the good old times of slavery, there is in my heart no taint of malice toward the ex-slaveholders. Many of them were not sinners above all others, but were in some sense the slaves of the slave system, for slavery was a power in the State greater than the State itself. With the aid of a few brilliant orators and plotting conspirators, it sundered the bonds of the Union and inaugurated war. Identity of interest and the sympathies created by it produced an irresistible current toward the cataract of disunion by which they were swept down. I have no denunciations for the past. The hand of friendship and affection which I recently gave my old master on his death-bed I would cordially extend to all men like him.

Speaking for my race as well as for myself, I can truthfully say that neither before the war, during the war, nor since the war have the colored people of the South shown malice or resentment toward the old slaveholding class, as a class, because of any or all the wrongs inflicted upon them during the days of their bondage. On the contrary, whenever and wherever this class has shown any disposition to respect the feelings and protect the rights of colored men, colored men have preferred to support them. No men from the East, West, North, or from any other quarter can so readily win the heart and control the political action of the colored people of the South as can the slaveholding class, if they are in the least disposed to be just to them and to faithfully carry out the provisions of the Constitution. They respect the old master class, but they hate and despise slavery.

The world has never seen a more striking example of kindness, forbearance, and fidelity than was shown by the slave population of the South during the war. To them was committed the care of the families of their masters while those masters were off fighting to make the slavery of these same slaves perpetual. The hearths and homes of those masters were left at their mercy. They could have killed, robbed, destroyed, and taken their liberty if they had chosen to do so, but they chose to remain true to the trust reposed in them, and utterly refused to take any advantage of the situation, to win liberty or destroy property. No act of violence lays to their charge. All the violence, crimes, and outrages alleged against the negro have originated since his emancipation.

Judging from the charges against him now, and assuming their truth, a sudden, startling, and most unnatural change must have been wrought in his character and composition. And, for one, I do not believe any such change has taken place. If the ex-master has lost the affection of the slave, it is his own fault. Men are not changed from lambs into tigers instantaneously, nor from tigers into lambs instantaneously. If the negro has lost confidence in the old master-class, it is due to the conduct of that class toward him since the war and since his emancipation. What has been said of the kindly temper and disposition of the colored people of the South to the old master-class, may be equally said of the feelings of the North toward the whole South. There is no malice rankling here against the South—there was none before the war, there was none during the war, and there has been none since the war. The policy of pacification of President Hayes was in the line of Northern sentiment. No American citizen is stigmatized here as a “carpet-bagger,” or “interloper,” because of his Southern birth. He may here exercise the right of speech, the elective franchise, and all other rights of citizenship as those to the manor born. The Lamars, the Hills, the Gordons, and the Butlers of the South may stump any or all the States of New-England, and sit in safety at the hearths and homes made desolate by a causeless rebellion in which they were leaders, without once hearing an angry word, or seeing an insulting gesture.

That so much cannot be said of the South is certainly no fault of the people of the North. We have always been ready to meet rebels more than half way and to hail them as fellow-citizens, countrymen, clansmen, and brothers beloved. As against the North there is no earthly reason for the charge of persecution and punishment of the South. She has suffered to be sure, but she has been the author of her own suffering. Her sons have not been punished, but have been received back into the highest departments of the very Government they endeavored to overthrow and destroy. They now dominate the House of Representatives, and hope soon to control the United States Senate, and the most radical of the radicals of the North will bow to this control, if it shall be obtained without violence and in the legitimate exercise of constitutional rights.

DISTINCTIONS THAT MUST BE PRESERVED.

Nevertheless, we must not be asked to say that the South was right in the rebellion, or to say the North was wrong. We must not be asked to put no difference between those who fought for the Union and those who fought against it, or between loyalty and treason. We must not be asked to be ashamed of our part in the war. That is much too great a strain upon Northern conscience and self-respect to be borne in silence. A certain sound was recently given to the trumpet of freedom by Gen. Grant when he told the veterans of Ohio, in a letter written from Milan, Italy, “That he trusted none of them would ever feel a disposition to apologize for the part they took in the late struggle for national existence, or for the cause for which they fought.” I admit that the South believed it was right, but the nature of things is not changed by belief. The Inquisition was not less a crime against humanity because it was believed right by the Holy Fathers. The bread and wine are no less bread and wine, though to faith they are flesh and blood. I admit further, that viewed merely as a physical contest, it left very little for self-righteousness or glory on either side. Neither the victors nor the vanquished can hurl reproaches at each other, and each may well enough respect and honor the bravery and skill of the other. Each found in the other a foeman worthy of his steel. The fiery ardor and impetuosity of the one was only a little more than matched by the steady valor and patient fortitude of the other. Thus far we meet upon common ground, and strew choicest flowers upon the graves of the dead heroes of each respectively and equally. But this war will not consent to be viewed simply as a physical contest. It is not for this that the nation is in solemn procession about the graves of its patriot sons to-day. It was not a fight between rapacious birds and ferocious beasts, a mere display of brute courage and endurance, but it was a war between men, men of thought as well as action, and in dead earnest for something beyond the battle-field. It was not even a war of geography or topography or of race.

“Lands intersected by a narrow frith

Abhor each other.

Mountains interposed make enemies of nations.”

But the sectional character of this war was merely accidental, and its least significant feature. It was a war of ideas, a battle of principles and ideas which united one section and divided the other: a war between the old and new, slavery and freedom, barbarism and civilization; between a government based upon the broadest and grandest declaration of human rights the world ever heard or read, and another pretended government, based upon an open, bold, and shocking denial of all rights, except the right of the strongest.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DECORATION DAY.

Good, wise, and generous men at the North, in power and out of power, for whose good intentions and patriotism we must all have the highest respect, doubt the wisdom of observing this memorial day, and would have us forget and forgive, strew flowers alike and lovingly, on rebel and on loyal graves. This sentiment is noble and generous, worthy of all honor as such; but it is only a sentiment after all, and must submit to its own rational limitations. There was a right side and a wrong side in the late war, which no sentiment ought to cause us to forget, and while to-day we should have malice toward none, and charity toward all, it is no part of our duty to confound right with wrong, or loyalty with treason. If the observance of this memorial day has any apology, office, or significance, it is derived from the moral character of the war, from the far-reaching, unchangeable, and eternal principles in dispute, and for which our sons and brothers encountered hardship, danger, and death. Man is said to be an animal looking before and after. It is his distinction to improve the future by a wise consideration of the past. In looking back to this tremendous conflict, after-coming generations will find much at which to marvel. They will marvel that men to whom was committed the custody of the Government, sworn to protect and defend the Constitution and the Union of the States, did not crush this rebellion in its egg; that they permitted treason to grow up under their very noses, not only without rebuke or repulse, but rather with approval, aid, and comfort—vainly thinking thus to conciliate the rebels; that they permitted the resources of the Union to be scattered, and its forts and arsenals to be taken possession of without raising a voice or lifting a finger to prevent the crime. They will marvel that the men who, with broad blades and bloody hands sought to destroy the Government were the very men who had been through all its history the most highly favored by the Government. They will marvel at this as when a child stabs the breast that nursed it into life. They will marvel still more that, after the rebellion was suppressed, and treason put down by the loss of nearly a half a million of men, and after putting on the nation’s neck a debt heavier than a mountain of gold, the Government has so soon been virtually captured by the party which sought its destruction.

OLD METHODS REVIVED.

And what is the attitude of this same party to-day? We all know what it was in 1860. The alternative presented to the nation then was, give us the Presidency or we will plunge the country into all the horrors of a bloody revolution. The position of that party is the same to-day as then. The chosen man then was John C. Breckinridge, of Kentucky. The chosen man of that party to-day is Samuel J. Tilden. The man to be kept out of the Presidential chair by threat of revolution was Abraham Lincoln. The man to be driven from the Presidential chair by the machinery of political investigation is Rutherford B. Hayes. Now, as then, the same rebellious spirit is much disturbed by the Army and Navy. In the first instance it was the policy to scatter, now it is to starve. The plotters of mischief hate the Army. It is loyal and true to the Republic.

This is not, as I have already said, a day for speech; certainly not for long speeches. Though the portents upon our national horizon are dark and sinister; though a somewhat reckless disregard of our national obligations and national credit [is] shown in the words and votes of some of our public men; though the temper and manner of the plantation, which talk of honor and responsibility, are increasingly manifest in legislative councils of the nation; though party strife and personal ambition somewhat distract the public mind; though efforts are being made tending to embroil capital and labor, and to antagonize interests which it is for the good of each to harmonize; though freedom of speech and of the ballot have for the present fallen before the shot-guns of the South, and the party of slavery is now in the ascendant, we need bate no jot of heart or hope. The American people will, in any great emergency, be true to themselves. The heart of the nation is still sound and strong, and as in the past, so in the future, patriotic millions, with able captains to lead them, will stand as a wall of fire around the Republic, and in the end see Liberty, Equality, and Justice triumphant.